It’s kinda

impressive that Disney has mass expansions and new attractions being planned

for just about every theme park they own. Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge is coming to

Disneyland and Hollywood Studios. Walt Disney Studios Park over at Disneyland

Paris is getting a major expansion in the next few years. The Magic Kingdom is

getting the Tron rollercoaster. Epcot is getting new attractions, even if it

means saying goodbye to its original theming. Mickey Mouse is getting a dark

ride of his own. Hong Kong Disneyland’s castle is getting rebuilt from the

ground up, and Tokyo Disneyland is getting a brand new Fantasyland. And Disney

California Adventure is getting the new refurbished Pixar Pier, and introducing

a new Marvel-themed land.

Disneyland’s

second gate sure has come a long way since its original opening back in 2001.

Frankly speaking, aside from Walt Disney Studios Park in Paris, it was perhaps

the most poorly conceived and welcomed theme park in the company’s history.

Safe to say, it was a disaster from day one, and needed ten years worth of

changes to get it up to the expected standards of a Disney theme park. But, how

did such a park come to be? Well, let’s go back to the days of cost-cutting,

creation-by-committee, and giant golden, sun-shaped hubcaps.

After

Disneyland’s opening and success in 1955, the land around Anaheim, California,

was snatched up by everyone hoping to get into the tourism business. The town

became urbanised, and some folks remain unhappy with the congestion and nightly

fireworks. Walt Disney didn’t like the idea of the real world intruding into

Disneyland, as views of motels and diners from the park would break the

illusion. He strived to resolve such issues during the development of Walt

Disney World. It had size for one, allowing him to create a huge project, which

would have included an airport and the unfulfilled EPCOT concept. Nowadays,

Walt Disney World has four theme parks, two water parks, numerous hotels, golf

courses, campgrounds, a shopping area, and tons of unused space which could

house a fifth theme park if Disney put their minds too it.

Disneyland,

on the other hand, was quite small, consisting of the park itself, the hotel,

and a large parking lot. By 1990, Disney’s management had changed several

times. The Disney founders were dead, and Walt’s son-in-law Ron Miller was

ousted from the role of CEO after years of the company gathering cobwebs. Enter

Michael Eisner, who took get strides to rebuild the company. His efforts led to

the Disney Renaissance, the rise of Pixar, and other such triumphs. But, the

theme parks, however, were another story.

Eisner

wishes to transform Disneyland into an impressive resort, complete with a

second theme park to be built over the car park. He wanted it to match Walt

Disney World in terms of success and giving guests a reason to stay longer.

But, the process to creating the second park was not an easy one.

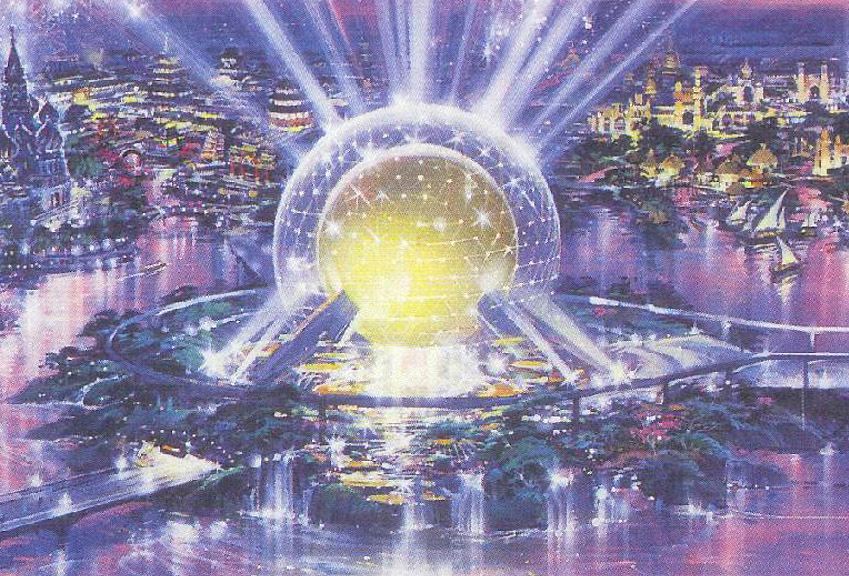

The first

planned proposal for the second gate was WestCot, a spiritual cousin to its

Floridian counterpart. A golden 300-ft tall Spacestation Earth would stand in

the middle, with themed lands reflecting a more modern future, and a united

World Showcase praised the four corners of the world, rather than individual

nations. It certainly sounded magnificent, like so many other unrealised Disney

dream projects. Disneyland’s expansion would have needed new ground, and would

have incorporated additions to the monorail, a new PeopleMover, new hotels, new

shopping complexes, the works.

But, there

was opposition to the expansion. For one, Anaheim residents were fed up with

Disneyland causing congestion on their roads, and a huge expansion would only

make things worse – even if it meant the introduction of new jobs and boost to

the town’s economy. Disney made alterations to WestCot to appease the

complainers, suggesting any congestions would be handled by highway ramps,

which would funnel guests directly into the resort’s future parking lots.

In 1995,

Eisner took a bunch of executives on a retreat to Aspen, Colorado. He still

hoped to turn Disneyland into a resort, but now on a much smaller budget. He

asked the executives to pitch ideas on what to do, including the second park. A

problem they had was with California itself. In Florida, Walt Disney World and

Universal Studios Florida were both major attractions, and sole reasons why

tourists visited the state in the first place. California, on the other hand,

had a variety of attractions outside of Disneyland. From Los Angeles, San

Francisco, national parks, and the Grand Canyon just a state away, California

had a lot to offer. But, Eisner wanted to people to stay in Disneyland longer.

He turned

to Paul Pressler for help. Pressler is perhaps the most hated person in Disney

history. After a career in merchandising and running the Disney Stores,

Pressler was promoted to being president of Disneyland, and then again to

Chairman of Walt Disney Parks and Resorts. Pressler was notorious for cost

cutting and fierce when it came to financing. He cut staffing, maintenance to

the park’s upkeep (which Walt was incredibly concerned about), closed

attractions, and valued the shops and restaurants than the rest. He was not a

creative man, he had experience running stores, not theme parks. To him, it was

just a larger Disney Store to run. So, naturally, it made sense for him to lead

the design plans for the second park. Of course.

Pressler’s

idea for the second park was simple. To prevent guests from leaving Disneyland

to explore the rest of California, they needed to bring California to them!

Disneyland

welcomed guests with that iconic train station and clock tower, taking guests

into the turn-of-the-century American streets of Main Street. DCA’s esplanade was

highlighted by monolithic but multicoloured letters which spelt out

“CALIFORNIA”. Not the most enchanting entrance, but the set of letters were

donated to the Friends of the California State Fair in 2012. It’s quite the

opposite of Disneyland. Disneyland is old timey, nostalgic, and whimsical.

Disney’s California Adventure was more aimed at the MTV generation, relying on

the same edginess and hipness that Jeffrey Katzenberg supported. The same mood

that nearly killed Toy Story before

it was made.

Onwards,

the park’s first land was Sunshine Plaza. The monorail passed over a

miniaturised replica of the Golden Gate Bridge. There were no attractions per

say. Just shops and restaurants blasting out modern music. Buildings were not

designed to resemble any specific period or theme, but were just painted

warehouses. Doesn’t exactly scream Disney. Funfairs have more flair to them. The

park’s early icon was a large bronze sculpture of the Sun, built over a water

fountain, but looked to some like a giant hubcap. It wasn’t a bad “weenie”, but

paled into comparison to Sleepy Beauty Castle, directly opposite from it in the

centre of Disneyland. The park seemed to do well with individual icons, but not

as a whole.

Hollywood

is obviously a big part of California, so it made sense to include such an

iconic place in the California-based park. But, Walt Disney World already had

Hollywood Studios, which captured the feel of a timeless Golden Age of Cinema

with its own Hollywood Boulevard. But, rather than copying its Floridian

counterpart, Hollywood Pictures Backlot in DCA decided to be a little more

urban and realistic. It went more for a fake studio lot design, complete with a

giant eyesore of a painted façade resembling a blue sky.

The largest

of DCA’s lands was the Golden States, consisting of a number of smaller lands.

These six areas were – Grizzly Peak, Condor Flats, The Bay Area, Pacific Wharf,

Bountiful Valley Farm, and the Golden Wine Vinery.

Condor

Flats was based around a modern day airfield set in the Californian desert.

But, rather than celebrate, say, the state’s history of aviation, it instead

upheld the cringeworthy pun-related edginess incorporated within the rest of

the park. It’s one success, and that of the whole park, was Soarin’ Over

California, which was later included in other Disney parks around the world (no

pun intended).

Perhaps the

most impressive sight in DCA is Grizzly Peak, a bear-shaped mountain that even

roared in the advertising. It doesn’t actually do that. Based around

California’s national parks, Grizzly Peak is currently the only land in DCA

that has remained mostly to its initial premise. But, rather than being a

romanticized tribute to one of America’s favourite pastimes, it suffers from

the same modern themes of the park. The sole attraction was, and still is,

Grizzly River Run, a generic ride with no story or animatronics. It could’ve

easily served as a Brother Bear ride

or something.

The Bay

Area was based around San Francisco, with the lone musical attraction, Golden

Dream, being housed in a replica of Bernard Maybeck’s Palace of Fine Arts. It

starred good old Whoopi Goldberg, playing Califa, the goddess which California

is named after, and gives a lesson on the history of the state.

And

finally, there was Paradise Pier, which did contain some action rides,

including California Screamin’. It had a lot of classic funfair/seaside pier

rides. But, this kinda feels like a contradiction to why Walt made Disneyland.

He found amusement parks and funfairs to be generic, noisy, and dirty. How

peculiar that Disney would make a land that is the complete opposite of why Disneyland

was created. The land also contains a unique ferris wheel, later donning Mickey

Mouse’s face, and becoming a secondary icon for the park.

Disneyland

took you to worlds of yesterday, tomorrow, and fantasy. Disney’s California

Adventure was a dumpster fire, with the humour of a Adam Sandler film, and the

creative effort of a group of pencil pushers. It recreated modern California,

with the culture and mood to match. Not to mention it was starved of funds,

made on such a cheap budget, likely fuelled by Eisner’s fear of failure

following Disneyland Paris’ unexpected failure. After opening day, word of

mouth soon spread about how poor DCA was, and it was an immediate failure.

Disney’s

California Adventure was dead on arrival, with only around five million guests

visiting it within the first year. Even then, only 20% of those guests were

satisfied with what they found in the park. Eisner’s cost-cutting and

Pressler’s team of marketers create a stillborn park. There were few

attractions, and those that were there at the start were either boring,

commonplace, or vilified. Seriously, who lists a tractor as an official

attraction in a Disney theme park? You find that sort of thing at a petting

zoo. Restaurants and shops were everywhere. An ugly, dated, edgy sense of

humour and a need to reflect modern California dominated every land and ride.

And there was no sense of that Disney charm that made its big brother so

beloved. It was more of a Six Flags than a Disneyland.

Just over a

year after Disney’s California Adventure opened, Disney started looking for

ways to improve it. By 2006, Eisner and Pressler were both gone, and Bob Iger

now ruled the roost. During the last few years of Eisner’s leadership, several

new IP-based rides were built in the park – A Bug’s Land, based on A Bug’s Life, The Twilight Zone Tower of

Terror, Turtle Talk with Crush, and a Monsters,

Inc. dark ride.

Iger saw

DCA as a failure, and considered two options – fuse both parks into one, with

Disneyland acting as an anchoring point for DCA, or to completely redesign the

struggling second gate from the ground up. Ambitiously, Iger chose the second

option. In 2007, Disney made plans to completely overhaul DCA with $600

million, even renaming it to Disney California Adventure. It would add in the

attractions and entertainment that the park had needed back in year one. And

importantly, the park’s lands would have their own narratives. Modernity and

bad puns were out the window. DCA was embracing the same passion and spirit

that went into Disneyland, and it came back big time.

Disney

California Adventure now had several new lands. It’s entry land was Buena Vista

Street, set in 1920s Hollywood, when a young Walt Disney came to town to make

cinematic history. Beautiful Californian architecture, water fountains, and the

red cars make up the new land. The shops and restaurants were re-designed, and

named after significant people and films in Walt’s early years of success. One

shop, a gas station, is named after Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, Walt’s first, lost

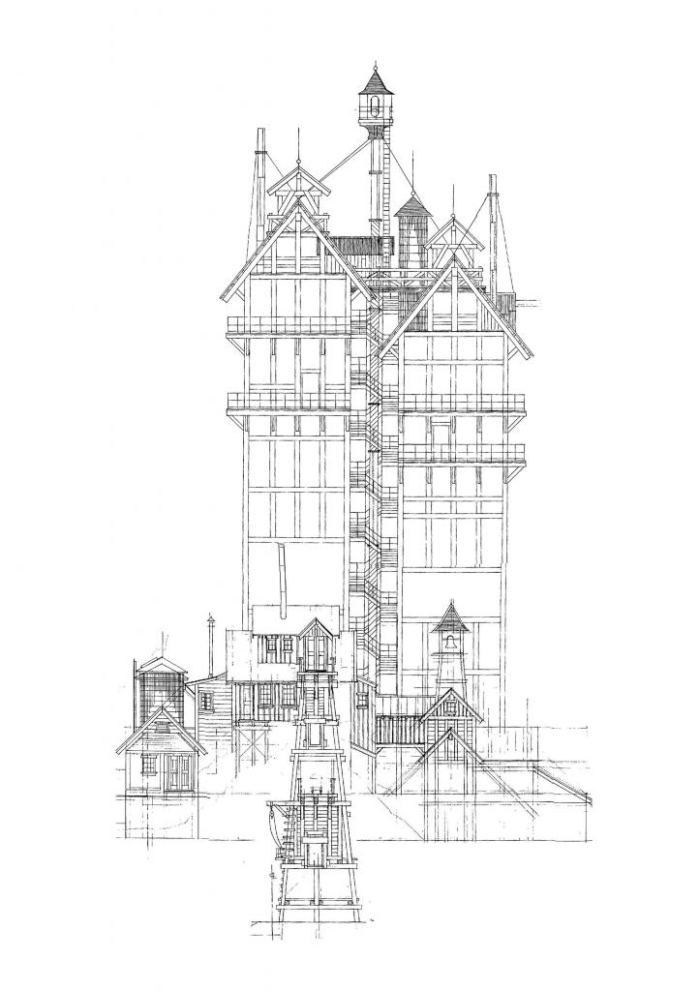

success, who was brought back home by Bob Iger. There is also the Carthay

Circle Theatre, based on the cinema of the same name, where Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

premiered and received a standing ovation.

Hollywood

Pictures Backlot became Hollywood Land. Gone were the wretched puns and such,

and instead it feels more like a genuine tribute to Tinsel Town and the golden

era of cinema. Aladdin: A Musical

Spectacular stayed a favourite in the Hyperion Theatre for years, but was

inevitably replaced by a stellar Frozen

musical. Frozen also had a habit of

taking over Muppet*Vision, the attraction’s show building being used to promote

new films. A Bug’s Land expanded, but is to close soon, and will be replaced by

an exciting new Marvel-themed land.

Even

Grizzly Peak received a facelift, ditching the modern extreme sports story, and

now setting it in a 1950s period. Though, Grizzly River Run still has a minimal

story. Condor Flats was absorbed into Grizzly Peak, reimagined as the Grizzly

Peak Airfield, now a forested, mountainous national park outpost. It also made

Soarin’ feel more appropriately themed.

Paradise

Pier was reimagined as well, becoming more timeless and perhaps acting as a

turn-of-the-century counterpart to Main Street. A number of the seaside

attractions were changed for the better, and the opening of Toy Story Midway

Mania and The Little Mermaid dark

ride made it hugely popular. And, each night, a brand new water show occurred in

Paradise Pier’s small lake – The World of Colour, a moving show of rainbow

coloured fountains, water screens, flamethrowers, and projections of Disney

films.

And the

newest land was Cars Land, incorporating the world of Cars, and a tribute to Route 66 as well. The level of detail is

amazing, and Radiator Springs Racers has become of the park’s most popular

attractions. The Tower of Terror closed and was reborn as Guardians of the

Galaxy: Mission Breakout, as the first part of the park’s future Marvel land.

Paradise Pier is also being transformed into Pixar Pier, still maintaining its

themes, but now with beloved Pixar characters around.

And, that’s

about it. The changes that have come to Disney California Adventure reflect the

attitude and business practices of Disney. Created as a cheaper resort

following the disappointment of Disneyland Paris, DCA had no artistic flair to

it, and was a soulless husk of a park made through dumb decisions, made by

mechanical, commercially-focused nitwits who have no place in The Walt Disney

Company. Turning Disneyland into a bigger resort was a good idea, but through

such an empty process and aiming at the wrong audience was not the way too go.

People

expect a certain level of standards at Disney theme parks, as Walt Disney did

with Disneyland: A place of yesterday, tomorrow, and fantasy, that takes guests

out of the real world for a while, and mostly hides it away to avoid breaking

the illusion. DCA did the exact opposite, abandoning those ideals in favour of

a grounded, modern-day sense of humour, and a blunt, flat, loveless look at the

state it was apparently celebrating. Hollywood was a drab, fake, uncreative

institution, the national parks were only relevant for extreme sports, and they

even put in a generic amusement park area. And they had a tractor as an

official attraction!

Thankfully,

the park deservedly failed, and Disney allowed their actual Imagineers to apply

bandages, and then build the whole thing from the ground. However, it is

possible that park’s dismal creation and failure can be justified. Michael

Eisner was clearly shaken by the commercial failure of Disneyland Paris, and

immediately pulled the plug on any major expansions or projects at all the

theme parks, perhaps out of fear of a repeated failure. Bigger was not always

better. Yes, Pressler and his team clearly had no knowledge or skills in

crafting a Disney theme park, but the limited space, reduced budget, and

consideration for the locals may have also been taken into account.

The idea of

celebrating California via a theme park was an interesting idea, but trying to

keep guests from going to see the actual sights of the state by creating

smaller versions seems a little redundant. And that lack of Disney magic and

sentimentality stained the park, even if its heart was mean to be in the right

place. Who wants to go to a Disney-grade resort and find a place filled with rubbish

attractions, no charm, no magic, awful wit, and a sense of cynical modernity

that has no place in Disneyland.

Eisner’s

micromanaging and cost-cutting would go on to affect both Walt Disney Studios

Park in Paris, and then Hong Kong Disneyland, both of which are slowly growing

to develop their own identities.

_KH3D.png/792px-Komory_Bat_(Spirit)_KH3D.png)